Notes on Japanese Book Formats

- Fenna Engelke

- Apr 8, 2021

- 3 min read

Updated: Jun 22, 2022

This post was created due to my current work placement at the Rijksmuseum paper conservation lab (a placement of 12 weeks between March and July), where I have been given a Japanese book to work on as part of my assignment there. These are some notes for myself on the subject of Japanese book formats as I work my way through the assignment.

This post will cover:

Japanese book formats and their terminology

More specific terminology and information about hanshi fukuro toji books, as it is relevant to my current assignment

Some introduction to the book I am working on while interning at the Rijksmuseum and how I did the condition reporting

Types of Book Formats

hand scroll (kansubon 巻子本)- standard Japanese hand scrolls measure around 30-50 cm. A ko-e (小絵) is a small hand scroll, measuring 15 cm. These smaller ko-e scrolls usually contain short stories, appearing at the beginning of the 14th century and reaching popularity in the 15th and 16th century.

accordion books (orihon 折本)- traditionally used for Buddhist sutras but also used for albums of calligraphy or paintings.

flutter book (sempuyo)- an accordion book, however with the front and back covers connected, creating a closed structure

butterfly book (dechoso or kochoso)- pasted leaf books which uses glue to keep the book together. The way the book opens do not allow the pages to open widely and can resemble butterfly wings, thus the iconographic name

pouch binding (fukuro toji 袋綴じ)- adapted from Chinese bookbinding. Sheets are printed on only one side and the pages are folded before being bound on the non-fold edge, creating a sort of 'pouch' between each page. There are variations in the binding designs, though four-hole stab bindings are more common.

hanshi- "half paper size", the most common book size for pouch bindings. The size can vary depending on when it was made but typically measure a 235 x 165 mm.

mino- larger format books, typically measuring around 280 x 200 mm.

Notes on hanshi fukurotoji bindings

inner binding (nakatoji) - The inner binding holds the text block together using a thread formed by twisted Japanese paper. This keeps the pages in the text block in place during the later thread binding and provides extra security to the book should the thread binding break or fail.

monks binding - used until the early 17th century. Creating small 'scew' like bits of Japanese paper to act as the inner binding.

corner pieces (kadogire) - corner pieces on the spine corners of hanshi bindings are made with fabric and are given a thin paper lining. On typically sized hanshi bindings they measure to about 9 mm along the top and bottom edge, and about 15 mm along the spine edge.

title strip (daisen) - The title strips are always top centered or left aligned. They measure to ~30mm wide with the length being 2/3 of the height of the book

Rijksmuseum Japanese Book Project

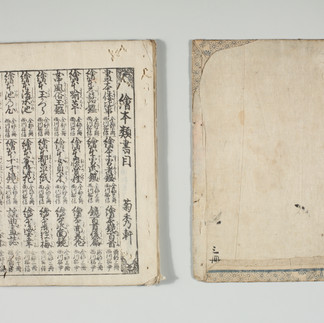

The book that was assigned to me for treatment is a four-station stab bound Japanese printed book, dating from January 1744. The book, Ehin Nezame gusa (translation: Picture book of sources of fitful walking), is the third part of a series and would have been used to assist readers in understanding classical works of literature through their use of imagery and poetry.

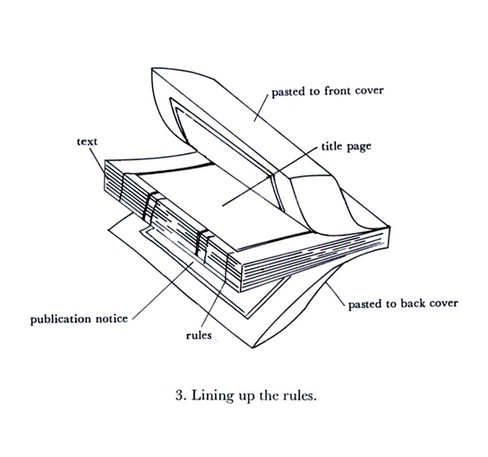

The diagrams seen in Japanese Bookbinding show a hanshi pouch book which has a full pouch leaves as flyleaves in the front and back of the book block. The object, however, dates from 1744. Books from the Edo period (1603 - 1868) tend to have single pages for their flyleaves, instead of the pouch-style leaf.[1] This can be seen in our object, where the front flyleaf is still present, though the back flyleaf is missing. However, there was some debate as to whether this page was a fly leaf at all or if it was a paste-down. Catherine Atwood's article notes that the paste-down sheets were often pasted only on the turned-in fore-edge of the cover. [2] There is some transfer of the printing pattern on the front cover turn-in onto the spare single sheet along the fore-edge so this may support the fact that this sheet is actually a paste-down. Additionally, Atwood mentions that there are no blank flyleaves in Japanese books, further supporting this possibility.[3]

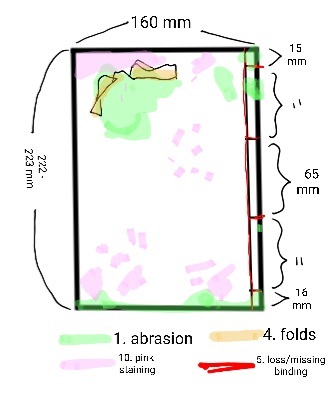

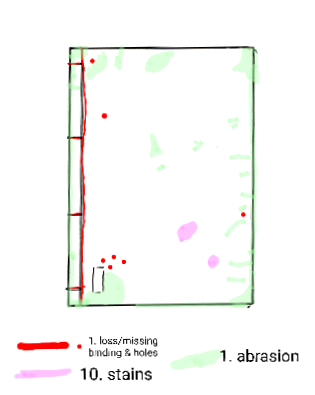

Because there was no Rijksmuseum standard for creating a condition report for Japanese books, I ended up taking diagrams from Ikegami's Japanese Bookbinding and edited them to suit the condition of the book, adding a key as I edited. I admit, I find it easiest to do these sorts of condition reports on my phone as I can easily draw in the notes with a stylus and can easily upload the finished image onto a drive to be later added to the report.

References

Bibliography

コメント