Conservation Up Close: The Making of Medieval Manuscripts

- Fenna Engelke

- Sep 28, 2023

- 4 min read

Updated: Oct 2, 2023

As the year moves forward so does the programming at the MFA. I gave myself some time to think between public programming and decided to focus on manuscripts for this Conservation Up Close session; partially inspired by my trip to the Care and Conservation of Manuscripts conference I attended back in April. Because I'm not yet an expert in our collections, I focused this session on the materiality of medieval manuscripts- talking to the public about parchment, pigments, and early European book formats. These two sessions were given on August 25th and September 8th to much public interest.

Hands-on Materials

I have found that I enjoy having a section of non-collection materials for people to touch and experience first hand. I usually have these tables separate from the tables with the museum objects on them so no one gets any ideas but I find that it might help with learning and relating to the objects.

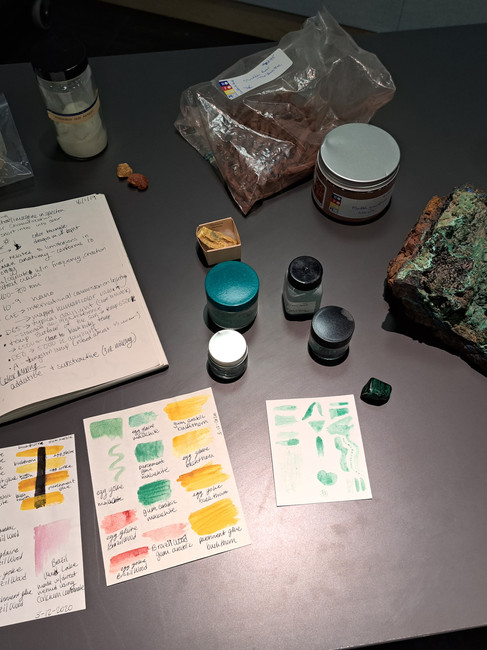

This time I had two tables of hands-on materials: one table with parchment, metal point tools, and some printouts of manuscripts showing scribes at work, and another table with materials related to pigments. The general public typically don't really know what parchment is so that discussion is always interesting. Having the metal point stylus was also a highlight that everyone seemed to love as I let them try them out on the printing paper I had at hand. The pigment materials consisted of stones traditionally used in pigment creation for medieval manuscripts as well as binders and bottles of ground pigments.

Museum Objects

The MFA doesn't have a huge collection of manuscripts but there are some great examples. Most of the material we have is late medieval but there was still enough to get my point across.

This small manuscript is my favorite in the collection which might surprise most; it has no illuminations and the reason I like has nothing to do with the interior pages. I love this book because it's a great teaching tool. Most of the more beautifully decorated manuscripts have been rebound at some point in their lives, but this book is a great example of what to expect when imagining medieval bindings. This manuscript has all the features I like to point out to the public: wooden cover boards, leather sewing supports, evidence of furniture. I also like to point out that this piece has pages that are flush with the size of the boards, lacking that size difference between cover and book pages that we are used to in modern books but would not have been done with with these medieval manuscripts.

The next book I like to share is a Spanish Psalter from the 14th century. This book has some more features I love; there are many signs of use in this book and it helps me highlight a great feature within manuscripts from this time, the re-use of materials. The pages are filled with patches which cover tears or losses in the book but the patches are always made from re-used manuscripts. The cover material itself is also likely a reused parchment cover, reused from a larger book, the cover material had been edited to now house this smaller psalter. One last feature I like to point out is the sewing within one of the parchment pages. Often done by the parchment markers, holes and tears in the parchment that occurred during parchment making process were often repaired by the makers before being sold to monasteries— another example of how precious every piece was for use.

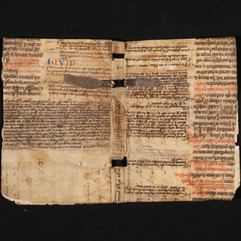

Alongside the manuscripts I also had single sheets of manuscript parchment that had been reused in various ways. In this case, one sheet seen here had been used as cover material for another book. The other pages seen above are manuscript pages that had been used as flyleaves for another book. I wanted to again highlight the reuse of material and also show that we find remnants of manuscripts often in this manner— cut up and reused in new ways.

Single sheet illuminations are easier to show to the public than the manuscripts at time and I decided to pulled out the reliable 57.707, an image of the crucifixion (a Leaf from the Potocki Psalter). We had done some XRF on the malachite in the image for teaching purposes and I often show this piece with the XRF readings next to it so I can explain how conservators can identify pigments. I chose some additional illuminations as well, the small illuminations from the workshop of Jacquemart de Hesdin. These four illuminations are so gorgeous and made with such detail I felt they were a great show of the skill and art that went into the making of illuminations.

MFA Objects

09.329. Homiliary, dated to about 1300-1350. Probably English.

17.516. Ferial Psalter, dated to about 1300-1350. Spanish.

RES.17.87

RES.17. 89

57.707 The Crucifixion (a leaf from the Potocki Psalter), mid 13th century. French. 43.212, 43.213, 43.214, 43.215. From the workshop of Jacquemart de Hesdin, dated around 1400. French

コメント